PHARMACOLOGICAL AND NON-PHARMACOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT OF ILD

PHARMACOLOGICAL AND NONPHARMACOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT OF ILD - Nurse connect

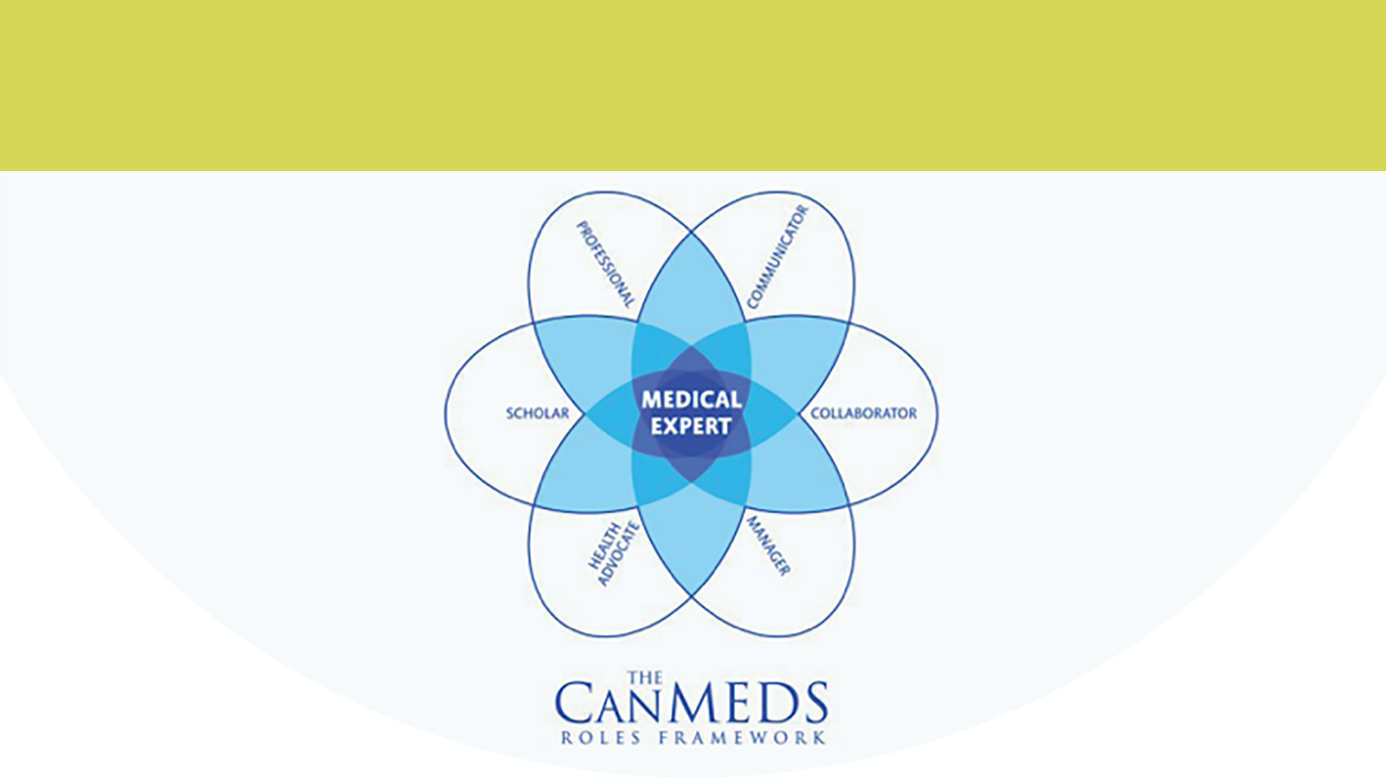

Interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) comprise a large and heterogenous group of disorders. Patients with ILD typically experience breathlessness, persistent cough, fatigue, anxiety, and depression.1 The management of ILD requires an individualized and multidisciplinary approach that takes into account the severity of ILD, presence of fibrosis, evidence of progression, comorbidities and patient’s preferences.2

|

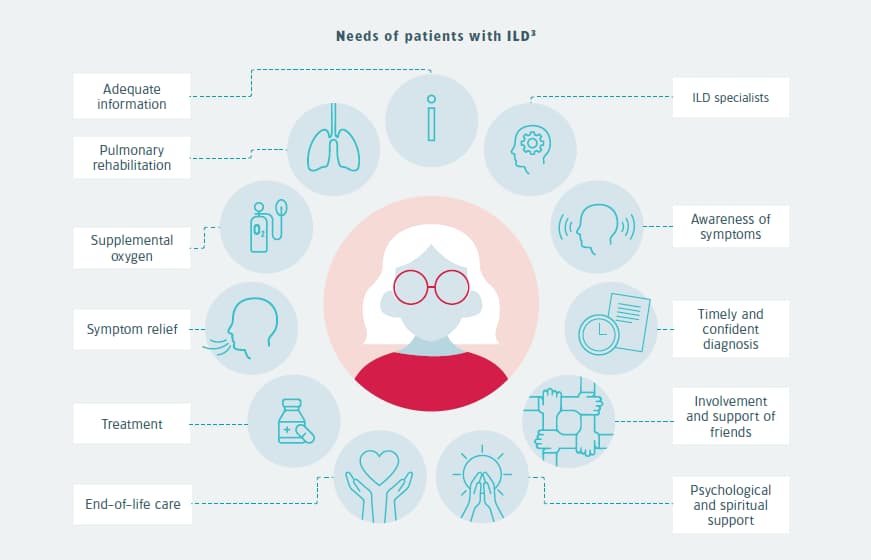

A holistic approach is essential to the management of ILDs.3 It means to provide support that looks at the whole person and adjust the treatment to the individual needs. Holistic care does therefore not only focus on the disease itself but also on the wellbeing of the patient. It may include a variety of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions to manage the disease, reduce symptoms, and/or improve quality of life.

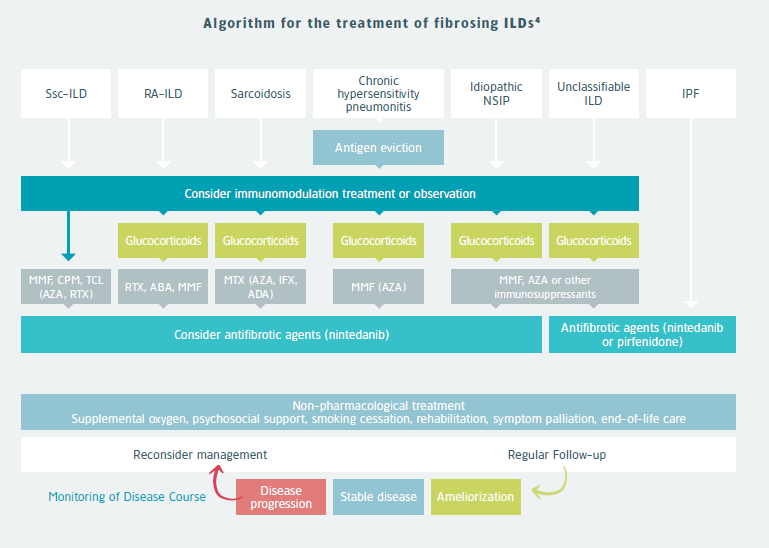

Management of the disease

The pharmacological treatment is guided by the underlying diagnosis and disease course. In most fibrotic ILDs with a suspicion of inflammation-driven disease, first-line therapy consists of immunomodulation with the use of glucocorticoids and/or immunosuppressive therapy. Preventing exposures and events that may drive further disease progression is also essential. For instance, avoiding the offending antigen is a priority in patients with chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis.4

Antifibrotic treatment

In IPF, antifibrotic treatment should be given immediately upon diagnosis.1 Antifibrotic treatment is considered in cases with progressive fibrosis despite appropriate first-line therapy. Nintedanib has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) for patients with SSc-ILD, and progressive fibrosing ILDs. It has shown to significantly slow down forced vital capacity (FVC) decline in patients with progressive lung fibrosis.5-8

Lung transplantation

Lung transplantation may be considered in patients with advanced pulmonary fibrosis who are relatively fit without relevant comorbidities.9 Extrapulmonary disease or severe coexisting conditions may disqualify some patients for lung transplantation, especially those with connective tissue disease (CTD).4

SUPPORTIVE CARE

Non-pharmacological management

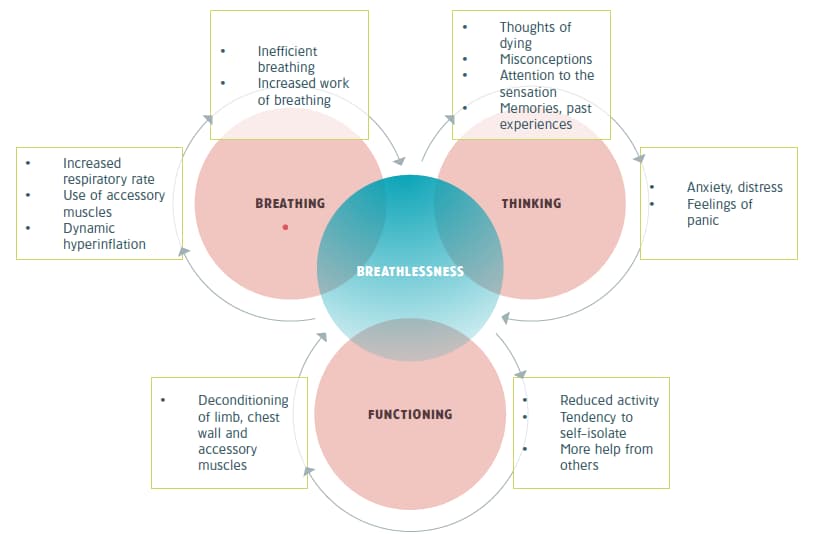

Non-pharmacological management should be considered throughout the disease course.4 Non-pharmacological care in chronic respiratory diseases mainly focuses on managing breathlessness and emotional well-being. The intensity of breathlessness is greatly influenced by reactions to the perception of breathlessness.10

As breathlessness does not solely depend on the severity of lung pathology, optimizing treatment of the underlying disease does not guarantee good symptom control.

|

MMF=Mycophenolate Mofetil; CPM=Cyclophosphamide; TCL=Tocilizumab; AZA=Azathioprine; RTX=Rituximab; ABA=Aba-tacept; MTX=Methotrexate; IFX=Infliximab; ADA=Adalimumab

Lifestyle

Diet

Malnutrition or weight loss are common in patients with pulmonary fibrosis and may negatively affect the quality of life. Moreover, losing muscle mass can accelerate the deterioration in lung function. Also, overweight patients may find it harder to breathe and exercise, which is associated with a decreased quality of life and worse health outcomes.11 A healthy diet is important for patients to prevent nutritional deficiencies and obtain or maintain a healthy weight.

Pulmonary rehabilitation

Pulmonary rehabilitation is an evidence-based, multidisciplinary and comprehensive medical intervention dedicated to patients with chronic diseases and reduced daily activity. The combination of pulmonary rehabilitation with an individualized treatment plan reduces the symptoms, improves physical fitness, enhancing the functional and psychological status, and quality of life of patients with ILD.12

Smoking cessation

Smoking is a risk factor for various lung diseases, including ILD. Cessation of smoking can improve outcomes in ILD and should be encouraged.13

Supplemental oxygen

In patients with fibrosing ILD hypoxia is common, even at rest in advanced disease. Despite little evidence, international guidelines recommend supplemental oxygen use in patients with severe resting hypoxia.14 As based on expert opinion, supplemental oxygen is indicated in patients with resting hypoxemia (PaO2 of <55 mm Hg, oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry of <89%, or PaO2 of <60 mm Hg and cor pulmonale or polycythemia).4 The main reasons for supplemental oxygen use would be to improve physical functioning and ultimately survival.14

Pulmonary rehabilitation and use of ambulatory oxygen in patients with isolated exertional hypoxemia has shown to improve the quality of life, reduce breathlessness, and increase walking ability.4

Vaccination

Vaccinations avoid infections that may worsen pulmonary fibrosis.9

Psychological and social care

The symptom burden and quality of life is not merely a consequence of the underlying physiological disorder but also depends on the patient’s adaptation to the illness.15 Psychological and lifestyle interventions can be used to prevent or reduce anxiety and depression. Improving patients’ skills and knowledge to manage their disease through self-management programs helps patients to carry out medical regimens specific to a long-term disease and guide behavioural change that improves well-being.16

For instance, cognitive behavioural techniques are increasingly incorporated into pulmonary rehabilitation programs to induce behavioural change.15,17

Dignity-conserving therapy can help reduce loss of self-esteem, the feeling of being a burden to others and can provide an opportunity to reflect on things that matter.17

Examples of questions used in dignity therapy:

What would you want your family to know and remember about you?

What are your most important accomplishments/at what times did you feel most alive?

What have you learned that you would want to pass on to others?

Also, attendance to peer support groups, online forums or pulmonary rehabilitation programs may be helpful. In some countries, there are nurse-led support and education programs, with initial reports suggesting high patient satisfaction.14

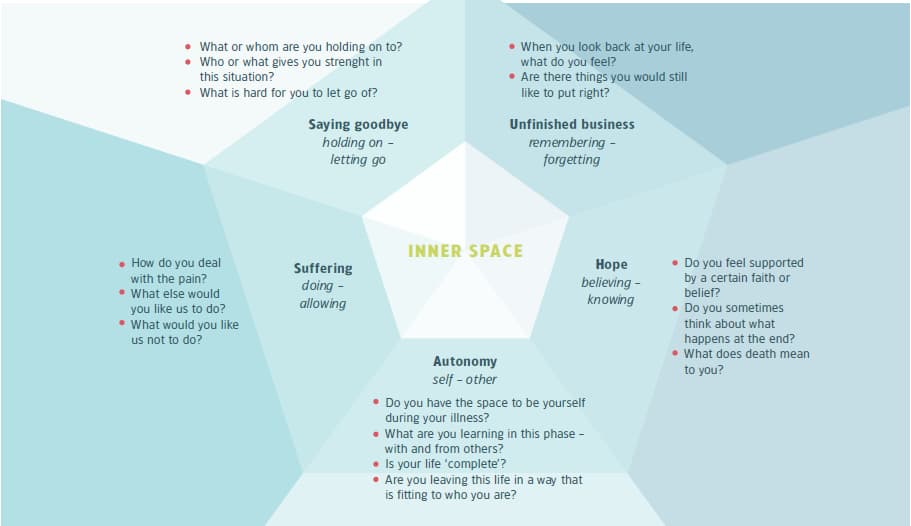

Support for religious and spiritual aspects

When faced with a chronic disabling condition, patients frequently express existential, spiritual and religious aspects. It is essential that healthcare providers recognise these needs and facilitate support if needed. Many hospitals have specialistic carers available to support patients of many cultural and religious backgrounds.

The diamond model provides sample questions regarding five themes in spiritual/existential matters.18

|

Managing fear and anxiety

The physical burden of chronic respiratory diseases pose significant challenges in daily activities, social relationships, self-perception and emotional functioning. Some patients adapt well to their disability, while others respond with fear, anxiety or depression.19 Depression and anxiety often go unrecognised and untreated. It is therefore important to explore patients’ fears and worries by asking questions.20

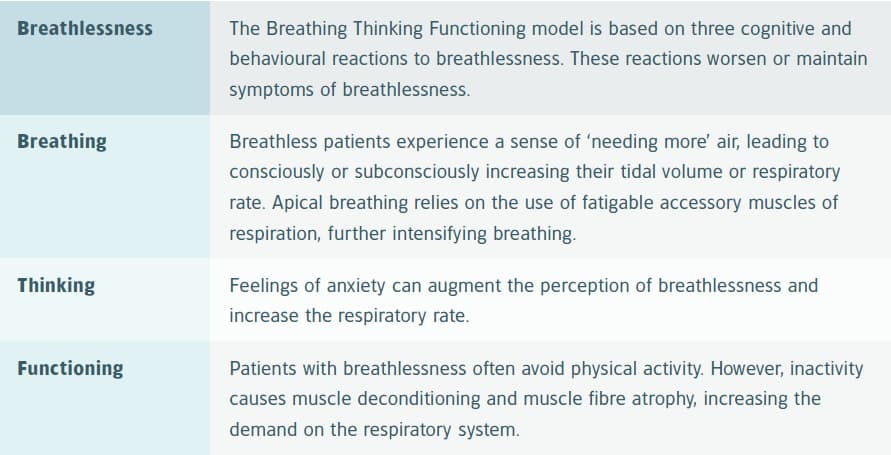

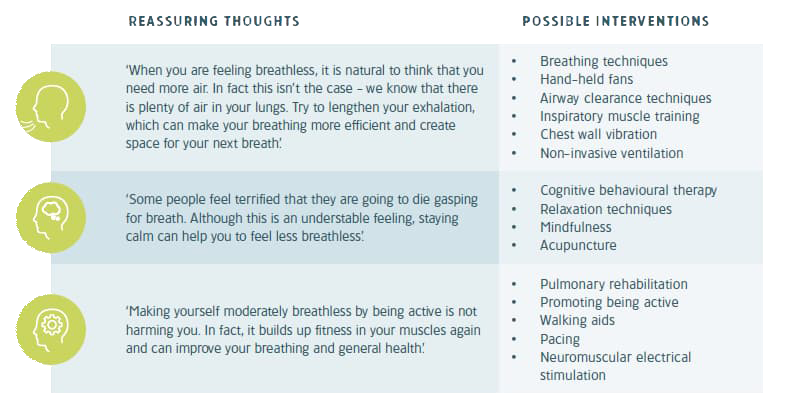

Managing breathlessness with thought

The Breathing Thinking Functioning model is a proposal, based on current evidence, that grasps the complexity of factors that perpetuate breathlessness. It therefore provides a rationale and focus to manage breathlessness.10

The Breathing Thinking Functioning model

|

|

The Breathing Thinking Functioning model can be used to explain mechanisms of worsening breathlessness and provide strategies on how to break the vicious cycle by behavioural change.10

Challenge misconceptions and provide non-pharmacological interventions for breathlessness10

|

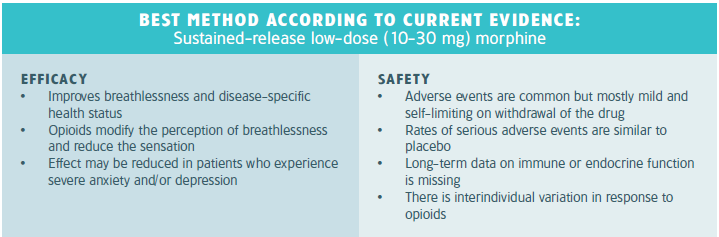

PHARMACOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT OF BREATHLESSNESS

International statements recommend the use of oral and parenteral opioids to treat refractory breathlessness despite optimal non-pharmacological treatment in advanced lung disease.21,22 However, patients with mild or moderate symptoms should first be managed with non-pharmacological treatments because long-term safety data of opioids is lacking.21,23,24 Studies support the use of sustained-release low-dose (10-30 mg) morphine in patients with severe breathlessness despite optimal non-pharmacological treatment.24,25

|

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines are widely used for the relief of breathlessness in advanced malignant and non-malignant diseases. There is however little evidence for the efficacy of benzodiazepines to relieve breathlessness.26,27 They may be considered as a second-or third-line treatment, when opioids and non-pharmacological interventions have failed to control breathlessness.27

REFERENCES

-

Wijsenbeek M, Suzuki A, Maher TM. Interstitial lung diseases. Lancet. 2022;400(10354):769-86.

-

Nambiar AM, Walker CM, Sparks JA. Monitoring and management of fibrosing interstitial lung diseases: a narrative review for practicing clinicians. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2021;15:17534666211039771.

-

Kreuter M, Bendstrup E, Russell A-M, et al. Palliative care in interstitial lung disease: living well. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(12):968-80.

-

Wijsenbeek M, Cottin V. Spectrum of Fibrotic Lung Diseases. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(10):958-68.

-

Distler O, Highland KB, Gahlemann M, et al. Nintedanib for systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(26):2518-28.

-

Flaherty KR, Wells AU, Cottin V, et al. Nintedanib in progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(18):1718-27.

-

Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2071-82.

-

Richeldi L, Kreuter M, Selman M, et al. Long-term treatment of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with nintedanib: results from the TOMORROW trial and its open-label extension. Thorax. 2018;73(6):581-3.

-

Cottin V, Crestani B, Valeyre D, et al. Diagnosis and management of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: French practical guidelines. Eur Respir Rev. 2014;23(132):193-214.

-

Spathis A, Booth S, Moffat C, et al. The Breathing, Thinking, Functioning clinical model: a proposal to facilitate evidence-based breathlessness management in chronic respiratory disease. NPJ primary care respiratory medicine. 2017;27(1):1-6.

-

Kanjrawi AA, Mathers L, Webster S, et al. Nutritional status and quality of life in interstitial lung disease: a prospective cohort study. BMC Pulm Med. 2021;21(1):51.

-

Wytrychowski K, Hans-Wytrychowska A, Piesiak P, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation in interstitial lung diseases: A review of the literature. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2020;29(2):257-64.

-

Hagmeyer L, Randerath W. Smoking-related interstitial lung disease. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112(4):43-50.

-

Wijsenbeek MS, Holland AE, Swigris JJ, et al. Comprehensive Supportive Care for Patients with Fibrosing Interstitial Lung Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(2):152-9.

-

Spruit MA, Singh SJ, Garvey C, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(8):e13-64.

-

Effing TW, Bourbeau J, Vercoulen J, et al. Self-management programmes for COPD: moving forward. Chron Respir Dis. 2012;9(1):27-35.

-

Maddocks M, Lovell N, Booth S, et al. Palliative care and management of troublesome symptoms for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2017;390(10098):988-1002.

-

IKNL. Summary of the guideline existential and spiritual aspects of palliative care.: Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organisation; 2019.

-

Hynninen MJ, Nordhus IH. Non-pharmacological Interventions to Manage Depression and Anxiety Associated with Chronic Respiratory Diseases: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Others. In: Sharafkhaneh A, Yohannes AM, Hanania NA, Kunik ME, editors. Depression and Anxiety in Patients with Chronic Respiratory Diseases. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2017. p. 149-65.

-

Baxter N, McMillan V, Halzhauer-Barrie J, et al. Planning for every breath. National Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Audit Programme: Primary care audit (Wales) 2015–17. London: RCP; 2017 December 2017.

-

Mahler D, Selecky P, Harrod C, et al. American college of chest physicians consensus statement on the management of dyspnea in patients with advanced lung or heart disease. Chest. 2010;137(3):674-91.

-

Jennings AL, Davies AN, Higgins JP, et al. A systematic review of the use of opioids in the management of dyspnoea. Thorax. 2002;57(11):939-44.

-

Verberkt CA, van den Beuken-van Everdingen MHJ, Schols J, et al. Effect of sustained-release morphine for refractory breathlessness in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on health status: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(10):1306-14.

-

Johnson MJ, Currow DC. Opioids for breathlessness: a narrative review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020;10(3):287-95.

-

Barbetta C, Currow DC, Johnson MJ. Non-opioid medications for the relief of chronic breathlessness: current evidence. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2017;11(4):333-41.

-

Abdallah SJ, Jensen D, Lewthwaite H. Updates in opioid and nonopioid treatment for chronic breathlessness. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2019;13(3):167-73.

-

Simon ST, Higginson IJ, Booth S, et al. Benzodiazepines for the relief of breathlessness in advanced malignant and non-malignant diseases in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10(10):Cd007354.